In large software organizations, technical documentation is commonly seen as someone else’s responsibility. Developers may recognize its importance, but the task itself typically belongs to a dedicated team of technical writers. For small software projects, however, and most critically for open source projects with limited resources, this distinction vanishes. Documentation becomes a responsibility of the developer or team writing the code, and its existence and quality are a direct factor in the project’s survival.

Frequently, a gap forms between the quality of available resources to make use of the software and the needs of its users (other developers contributing to the project or using it for their own solution). When documentation is missing or outdated, contributors are left to guess, leading to frustration and, ultimately, abandonment in favor of better-documented alternatives. It’s as if Ikea sold furniture without including the assembly instructions; would you still buy an Ikea bed knowing the struggle ahead? All too often, documentation is the first thing to be neglected in a project and in many cases, the “people don’t read documentation” argument is used to justify this neglect. Here’s the thing: while novice users may not read, experienced users rely on documentation.

Without this foundational content, the support burden shifts to less efficient channels. Maintainers and contributors find themselves trapped in forums answering the same questions repeatedly, or worse, confronted with the gatekeeping “just look at the code” or “works for me” mentality. This creates a vicious cycle where the lack of documentation leads to more questions, which in turn leads to exasperation and the eventual decline in the project’s user base.

Why developers struggle with documentation

My first steps in documentation began not in a technical writing role, but on the front lines as a support engineer for Microsoft SQL Server. Personally, one of the most rewarding aspects of this job was writing knowledge base articles to help users solve technical problems themselves (a task made significantly harder when the only “AI assistant” was a Google search). It was a perfect introduction to the craft, as those articles all followed a simple, predictable structure: problem, workaround, solution.

When I later transitioned into a full-time writing career, that straightforward structure was no longer enough. I was suddenly responsible for a wider array of technical documents that demanded more complex designs. Eager to learn the craft formally and master these new challenges, I read every book and manual I could find on the topic. But I soon discovered a problem. With rare exceptions (Mark Baker’s Every Page Is Page One among them), most resources fell short of addressing the questions of novice technical writers. The rules for syntax and bullet points were there, but the most critical part of the process, how to decide what to write and how to structure it, was missing. It felt like I wanted to write a novel, but all I was given was a grammar book. Now, after more than a decade in the field, I see that this problem still exists, especially for developers who are expected to write.

The idea that developers don’t write documentation because they are lazy or don’t enjoy writing is an oversimplification. I know many developers who understand the importance of documentation and are actively looking for ways to improve it. They struggle because they know how fundamental documentation is to their project’s success but, at the same time, they feel overwhelmed by the task. This is especially true for those in small, resource-constrained projects typical in the open-source world.

While many factors contribute to this challenge (competing incentives, lack of time or motivation, or even the curse of knowledge) I believe the root cause is a single, powerful blocker: ambiguity. Writing code is a discipline of predictable outcomes; it either compiles or it doesn’t. Documentation, by contrast, often feels like a murky process with no clear rules.

When a developer, who is an expert in a logical and structured domain, is asked to document a feature, they’re confronted with a series of ill-defined questions:

- The “What”: What content do I actually need to write? A single page? A new section with five pages? The scope is undefined, making the task feel open-ended and overwhelming from the start.

- The “How”: How should I organize this information? What comes first? A user’s ability to understand a document is strongly dependent on its structure, yet most guides don’t help here.

- The “Where”: Where does this new content fit? Our documentation site has dozens of pages, many times in different systems. Without a clear map, developers are rightly concerned that their work will be lost in a sea of content.

These aren’t really writing problems; they’re design problems. Before a single word is written, someone needs to decide the structure: what type of document is needed, how information should flow, and where it fits in the overall system. Without that design step, writing feels unbounded, and developers will naturally prioritize the work where the rules are clear and the outcomes are predictable: writing code.

From content to design: shifting the focus

Researchers in technical communication have shown for decades that design shapes how people understand and use information. Their findings give us a foundation for a design-first approach to documentation. As early as 1996, in her seminal book Dynamics in Document Design, researcher Karen A. Schriver provided clear evidence for this approach. In user studies of real-world documents, she demonstrated that good information design is a critical component of usability. Readers consistently performed tasks faster and understood information more accurately when using documents with a clear visual hierarchy and logical chunking of information. Schriver’s studies show that walls of text raise cognitive load and hide what users need.

Schriver’s findings are part of a larger conversation about the importance of design in technical communication. In his work on The Nurnberg Funnel, John M. Carroll argued for a content design philosophy that prioritizes a highly structured layout over comprehensive descriptions. More recently, this idea has been modernized by authors like Michael J. Metts and Andy Welfle in their book Writing Is Designing. They argue that all user-facing text (from the label of a button to a paragraph in a help guide) is a critical part of the user experience.

However, despite all this evidence, technical communication still tends to focus on text production rather than information design. Many writers and developers asked to write default to thinking in terms of words, sentences, and pages. The ingrained habit is “produce content,” not “design an information flow.”

This is why we need a shift. Documentation must be treated as design first, writing second. And this principle is more relevant than ever: with Large Language Models (LLMs) now capable of producing raw text, our value lies in being the architects, not the bricklayers. The structure, not the content, must come first.

Making design-first documentation practical

This proposed playbook translates that shift into four concrete stages that guide developers from idea to published docs.

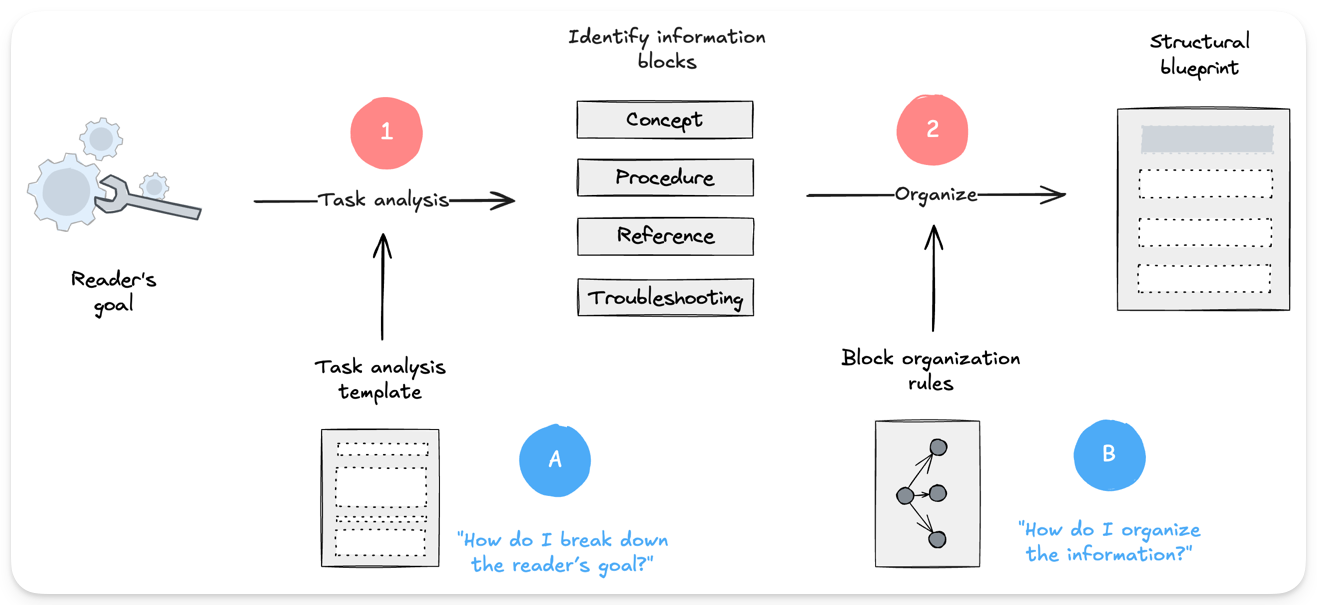

- Stage 1: Designing the information. Before writing a single word, the developer identifies the reader’s goal, performs a guided task analysis (1, A), and breaks it down into core informational building blocks (Concept, Procedure, Reference, Troubleshooting). These blocks are then organized (2, B) into a structural blueprint for the content. The result is a clear content organization plan that directly answers the question: “How should I organize the information?”

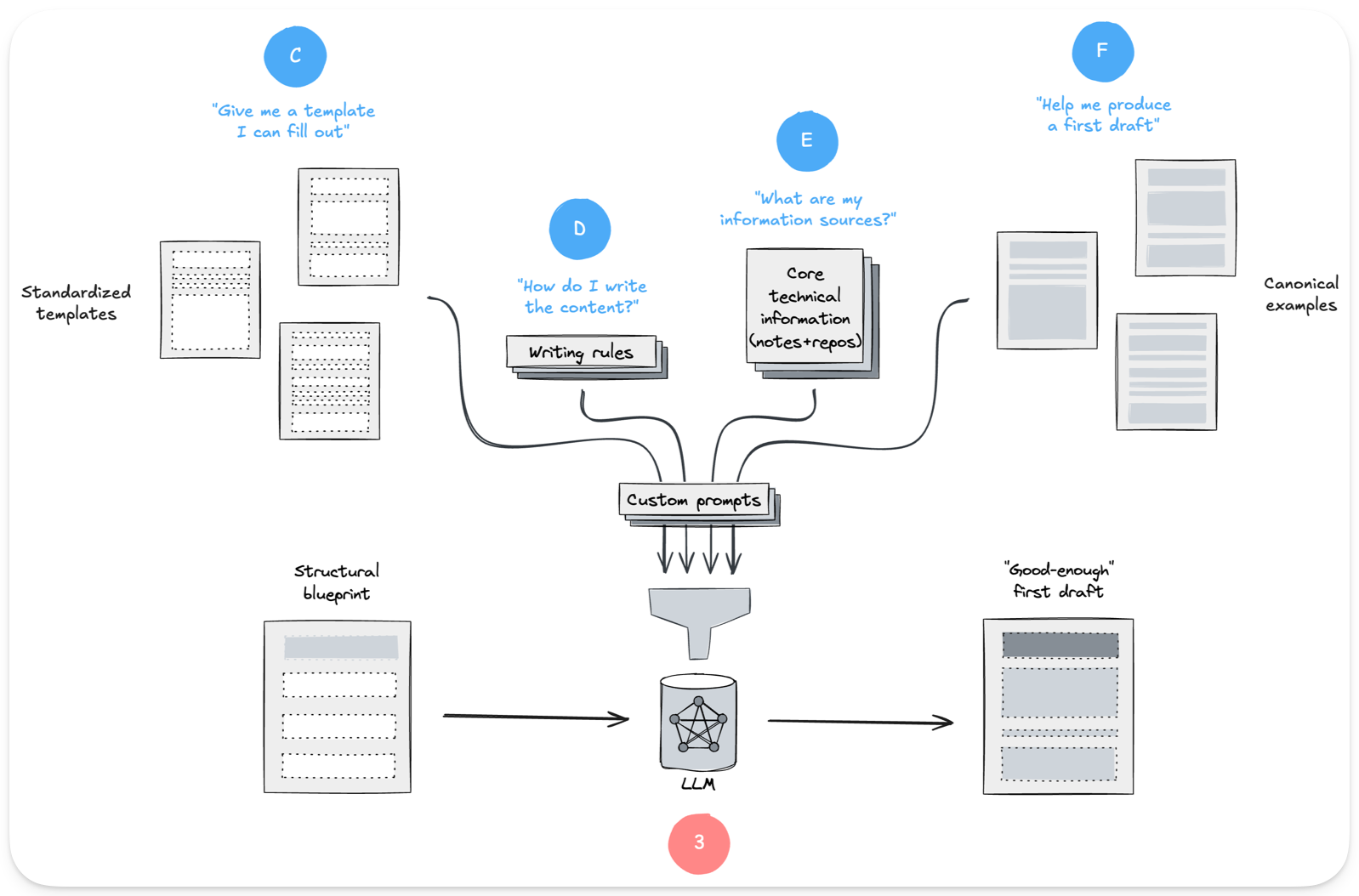

- Stage 2: Populating the content structure. In this stage, the structural blueprint becomes a “good-enough” first draft. Developers use standardized templates (C) and canonical examples (F) that define the layout and flow, then populate them with content drawn from core technical sources (E). LLMs (3) often assist by filling in text with customized prompts. The output is a draft that directly answers the question: “What content do I need to write?”

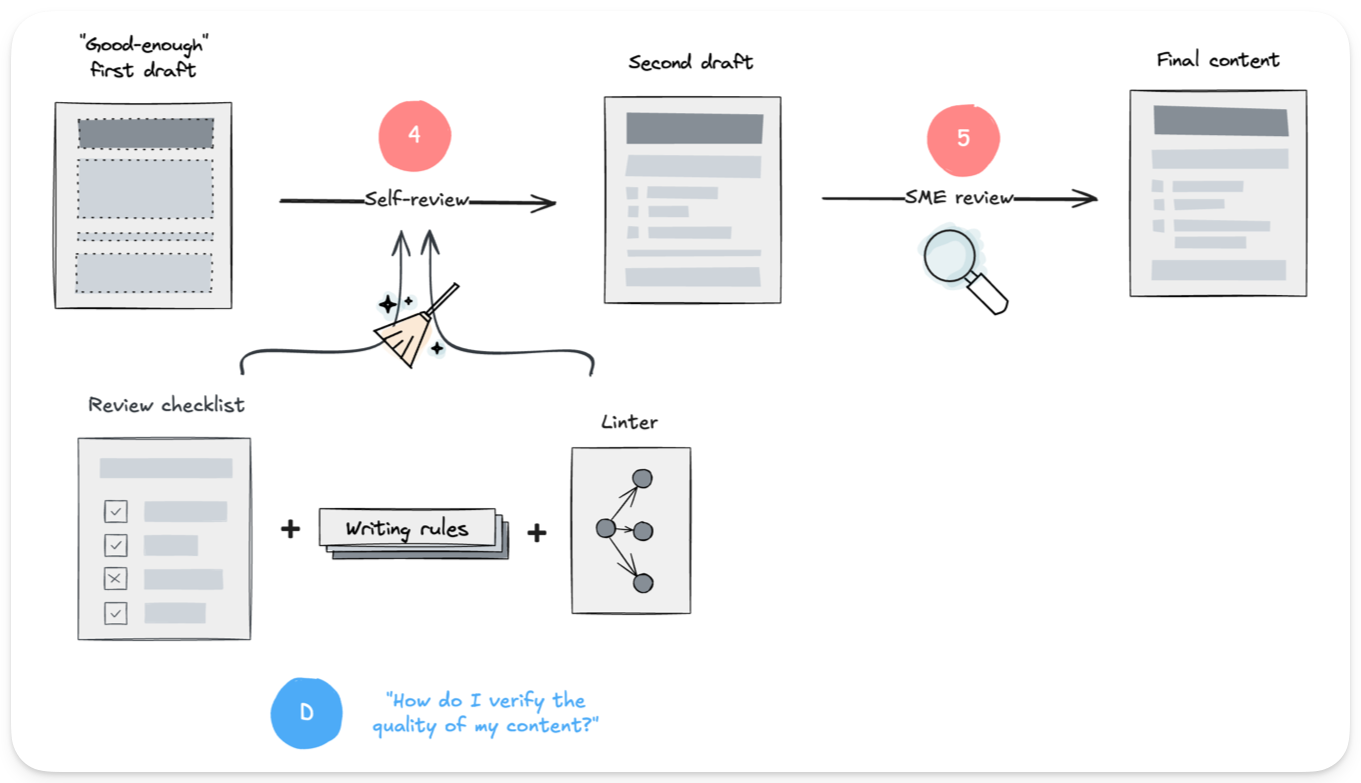

- Stage 3: Validating the design. Authors first self-review the draft (4), using checklists, writing rules, and linters (D) to improve clarity and structure, sometimes with additional LLM assistance. Subject-Matter Experts (5) then review for technical accuracy and confirm that the content organization effectively guides the user. Reviews happen through a GitHub pull request.

- Stage 4: Integrating into the overall structure. In this stage, the approved document is added to the documentation site (6). The content model (E) defines its location and relationship to other content, answering the question: “Where does this new content fit?” The result is documentation that is not only written, but also organized and discoverable.

At the core of this design-first workflow are the practical tools that help novice writers: templates to define the document’s architecture, examples to provide a clear target, and checklists to ensure every piece is in place. The goal is to transform documentation from a seemingly ambiguous process into a carefully designed one, mirroring the principles developers already know: clear rules, reusable components, and a structured approach.

“But is it AI-ready?”

You might be wondering if Artificial Intelligence (AI) doesn’t render all these obsolete. Isn’t AI doing this work, after all? The short answer is: not completely. While generative AI is a revolutionary assistant for writing and polishing content, it does not replace a human-led design process. At least, not today.

Since ChatGPT was released, I have been testing AI extensively for documentation design and authoring. While the results can appear effortless and flawless to inexperienced eyes, the reality is more nuanced. AI excels at generating fluent text from a given context, but it struggles to produce high-quality, structured documentation consistently. Models can be inconsistent, and even with the same prompt, the results can be a mix of brilliant and unusable. This is the reason a documentation playbook for developers should count on LLMs but not fully rely on them. Hence, the importance of templates, examples, and checklists.

I am not a Luddite. I use AI daily, and as someone with more gadgets in my drawers than is reasonable, I embrace technology that makes my work and life better. But with all the hype around AI, it’s easy to think it will soon be able to handle these tasks all by itself. This perspective overlooks that work is much more than the result of raw intelligence. With proper guidance, AI can be an extraordinary tool in many areas, and sometimes using it feels like magic. I am writing this very post with the help of an LLM; it’s an extraordinary partner for refining sentences and exploring ideas, but the need to write them and how to organize them are ultimately mine. This is the most effective model for documentation today: a partnership where human design guides AI execution.

Templates, examples, and checklists reduce ambiguity, for people and for LLMs. It’s no coincidence that the core components of this playbook are precisely what LLMs need to be effective. Both novice human writers and powerful AI models struggle with the same fundamental problem: ambiguity. The work we do to create clarity for a human developer, it turns out, is the exact same work required to effectively guide a machine. This makes our design-first system inherently AI-ready.

What’s next?

This documentation playbook is a practical workflow that Chen (@chen06324) and I (@campo4171) are actively developing to help IFT teams create high-quality documentation more efficiently. You can expect to hear more about it in the coming months.

By shifting our focus from writing to design, we turn documentation into a predictable, logical process; something developers can approach with the same confidence as coding. To make this real, we need more than a workflow: we need a shared mindset. At IFT, documenting is not “extra work”; it’s part of building the software itself. The culture we build together will decide whether our projects are merely usable, or usable and sustainable.